John’s Note: The early colonists found turkeys so plentiful that hunters didn’t have to call in the birds to take them. A Massachusetts settler in the 1600s might see 1000 turkeys in a day close to his home. New York City in the mid-1700s held an annual Christmastime turkey shoot between where Park Row and the end of the Brooklyn Bridge lay today. The area just outside NYC at that time often held turkeys traveling in flocks of hundreds with some weighing 30 to 40pounds each. Although the human voice was probably the first device ever used to call a wild turkey, Indians and settlers sometimes called turkeys by blowing across briar leaves to make yelping sounds. But even today, some proficient turkey callers use nothing but their voices to call gobblers.

The late Ben Rodgers Lee, of Coffeeville, Alabama, once one of North America’s leading turkey callers and call manufacturers, utilized his voice when hunting gobblers long before he started crafting turkey calls.

The late Ben Rodgers Lee, of Coffeeville, Alabama, once one of North America’s leading turkey callers and call manufacturers, utilized his voice when hunting gobblers long before he started crafting turkey calls.

Asked why he made turkey calls when he called toms so effectively with his voice, Lee responded, “I consider myself one of a small number of people who can successfully call a turkey with my voice. Also, I can’t sell my voice, but I can sell turkey calls.” Just about anything that squeaks, squawks or cries can and will call a wild turkey, with some calls more effective than others. The hunter who masters the diaphragm or slate call has a better chance of killing a turkey than a fellow who rubs two sticks together until they squeak.

Box Call:

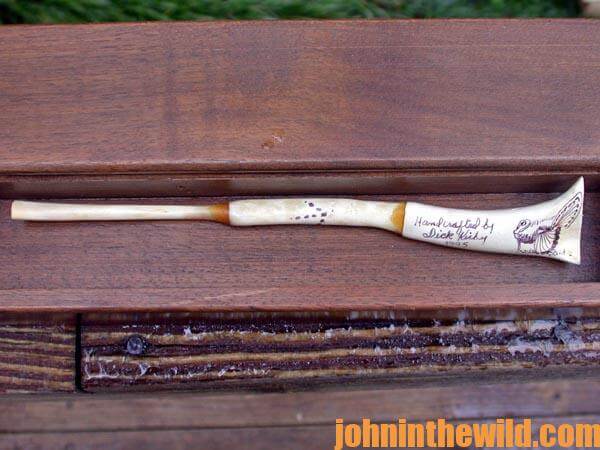

In years past, avid turkey hunters often crafted cedar box calls. For instance, M.L. Lynch, of Homewood, Alabama, founder of M.L. Lynch Calls, developed a box call in the early 1900s. At that time, people generally whittled box calls out of cedar. However, this type of call had a built-in problem when anyone tried to make two box calls that sounded the same.

A hunter who owned a fine box call realized he never might find another just like it. The hollowed out box usually had  some type of paddle that slid across the top and made clucks, whines, yelps and squeaks. However, in these early models, the lids, or paddles, rarely had the same thickness or density. Also, the thickness of the walls of the box varied greatly, as did the bottom of the call. The turkey hunter who discovered a box call that made just the right sound considered it a treasure to guard well.

some type of paddle that slid across the top and made clucks, whines, yelps and squeaks. However, in these early models, the lids, or paddles, rarely had the same thickness or density. Also, the thickness of the walls of the box varied greatly, as did the bottom of the call. The turkey hunter who discovered a box call that made just the right sound considered it a treasure to guard well.

When Lynch began to work with box calls, he thought of the problems and frustrations he had had with them. Then he made a breakthrough that changed the crafting of all box calls. Mr. Lynch realized the lids, walls and bottoms of the calls needed some kind of uniformity. Instead of taking one piece of wood and carving out the center, he planed–down individual pieces of wood to make them the same thickness. When he had these parts planed to the proper density, he glued each box together. Although this technique sounds simple today, at the time no one else used such a revolutionary method. Lynch developed a way to make all box calls sound alike and to mass-produce easy to use calls.

Mouth Diaphragm Call:

In the late 1920s, a hunter named Jim Radcliff, Sr., was bitten by a mad dog in Mobile, Ala. That event wouldn’t warrant any space in this information except that Radcliff’s favorite sports included hunting turkeys. While in New Orleans receiving daily injections for rabies, Radcliff had time on his hands and nothing to do. He visited Bourbon Street. In the French Quarters, he found something that helped revolutionize the sport of turkey hunting once more. Noticing a man standing on the corner with a small tin cup in front of him, Radcliff listened closely as the entertainer made some of the most beautiful bird calls Radcliff ever had heard.

When Radcliff asked the musician if he could make the sound of a wild hen turkey, the street performer had to answer no. But he could imitate a mockingbird, a redbird, a crow, a warbler, a sparrow and almost any other bird known to man. Radcliff went to his hotel and returned with one of his box calls. After listening to Radcliff’s calling on the box, the man decided he probably could imitate a hen turkey.

The bird caller, who had used a mouth diaphragm, returned to his room and fashioned a mouth call to sound like a hen turkey. After practicing for 2 or 3 days, the musician played those sounds for Radcliff on a device made of lead, prophylactic rubber and cloth tape. The pure sound of the call convinced Radcliff he had to have one. The street performer taught Radcliff how to use the call and how to make his own diaphragm calls.

From this humble beginning evolved several generations of mouth diaphragm calls, including the single reed, the double reed, the triple reed, the split reed and the stack call.

To get John E. Phillips’ eBook “PhD Gobblers,” click here.

About the Author

John Phillips, winner of the 2012 Homer Circle Fishing Award for outstanding fishing writer by the American Sportfishing Association (AMA) and the Professional Outdoor Media Association (POMA), the 2008 Crossbow Communicator of the year and the 2007 Legendary Communicator chosen for induction into the National Fresh Water Hall of Fame, is a freelance writer (over 6,000 magazine articles for about 100 magazines and several thousand newspaper columns published), magazine editor, photographer for print media as well as industry catalogues (over 25,000 photos published), lecturer, outdoor consultant, marketing consultant, book author and daily internet content provider with an overview of the outdoors.