The call of the elk, an eerie-sounding, high-pitched whistle usually followed by a series of guttural grunts, is a romantically wild symbol of the high country where the elk live. Although elk appear to be big and clumsy, weighing up to 1100 pounds and standing about 5-feet tall at the shoulders with a length of 7 to 7-1/2-feet, they can trot and gallop for short periods at 45 mph before tiring.

The call of the elk, an eerie-sounding, high-pitched whistle usually followed by a series of guttural grunts, is a romantically wild symbol of the high country where the elk live. Although elk appear to be big and clumsy, weighing up to 1100 pounds and standing about 5-feet tall at the shoulders with a length of 7 to 7-1/2-feet, they can trot and gallop for short periods at 45 mph before tiring.

The Algonquin and Shawnee Indians called these animals wapiti, which means white rump, because of the light-colored patch of hair surrounding the elk’s tail. The early English colonists gave the wapiti the name elk that originally belonged to the European moose. When Columbus got off his boat in the New World in 1492 after sailing from the Old World, elk hunting was easy. More than 10-million elk lived from the Blue Ridge Mountains of the East to the vast West. However, by the time the Lewis and Clark Expedition took place in 1806, elk almost had vanished from the East. This decline of elk was a result of intense market hunting done for elk hides (merchants shipped 33,000 elk hides at a time down the Mississippi River in the 1800s), meat and antlers as well as the loss of elk habitat and the encroachment of civilization. Also some entire herds of elk were wiped out for their small, upper teeth that resembled tiny ivory tusks that jewelers used extensively at one time.

By the beginning of the 20th century, only about 100,000 elk were left in seven western states with the eastern and the Merriam’s subspecies already extinct before the Lacy Act was passed by Congress in 1901 outlawing market hunting in the U.S. Careful management by the government and state wildlife agencies as well as conservation-minded citizens like the Boone and Crockett Club https://www.boone-crockett.org/ and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation https://www.rmef.org/ brought the elk herd nationwide to 500,000 animals in the late 1970s. The adaptability of elk to live in semi- desert shrublands, plains and high mountains also aided their increased numbers.

By the beginning of the 20th century, only about 100,000 elk were left in seven western states with the eastern and the Merriam’s subspecies already extinct before the Lacy Act was passed by Congress in 1901 outlawing market hunting in the U.S. Careful management by the government and state wildlife agencies as well as conservation-minded citizens like the Boone and Crockett Club https://www.boone-crockett.org/ and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation https://www.rmef.org/ brought the elk herd nationwide to 500,000 animals in the late 1970s. The adaptability of elk to live in semi- desert shrublands, plains and high mountains also aided their increased numbers.

Today about 1.2 million elk live in the U.S., and many are in herds in 11 eastern states. However, I believe every one of those elk, known as advanced wapiti and the second largest species of the deer family with only the moose bigger, must hide behind a tree or a bush or hole-up in some deep mountain cave out of my sight. Most easterners believe that since elk are so large they should be easy to find and hunt. But those easterners never must have climbed high mountains, waded icy creeks, breathed thin air or tried to push their aching muscles past the point of fatigue to catch-up to the bugling sound of the elk that lures hunters – much like the sirens’ calls lured the ancient Greeks to the rocks of disaster.

The elk’s powerful legs and the design of its feet make the animal agile in mountains. Although color-blind, they do rely on their ability to see movement to help them flee trouble. The elk’s most-developed sense – that of smell – allows it to detect enemies easily. The animal also utilizes its acute hearing effectively. Another asset the elk has is its single-foot gait that lets it move at 20 miles per hour without tiring. The elk lifts each foot and puts it down alone and easily outdistances men running at 15 mph, usually about the top speed of humans.

The elk’s powerful legs and the design of its feet make the animal agile in mountains. Although color-blind, they do rely on their ability to see movement to help them flee trouble. The elk’s most-developed sense – that of smell – allows it to detect enemies easily. The animal also utilizes its acute hearing effectively. Another asset the elk has is its single-foot gait that lets it move at 20 miles per hour without tiring. The elk lifts each foot and puts it down alone and easily outdistances men running at 15 mph, usually about the top speed of humans.

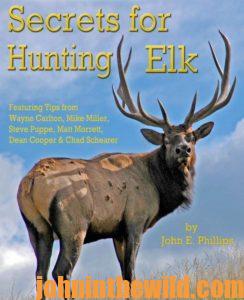

To learn more about hunting elk successfully, check out John E. Phillips’ book, “Secrets for Hunting Elk,” available in Kindle and Audible at https://www.amazon.com/. You may have to copy and paste this click into your browser. (When you click on this book, notice on the left where Amazon allows you to read and hear 10% of the book for free). On the right side of the page and below the offer for a free Audible trial, you can click on Buy the Audible with one click.

To learn more about hunting elk successfully, check out John E. Phillips’ book, “Secrets for Hunting Elk,” available in Kindle and Audible at https://www.amazon.com/. You may have to copy and paste this click into your browser. (When you click on this book, notice on the left where Amazon allows you to read and hear 10% of the book for free). On the right side of the page and below the offer for a free Audible trial, you can click on Buy the Audible with one click.

Tomorrow: Confessions of Elk Hunter Chad Schearer